Before watching Studiocanal’s new restoration of the 30-year-old science-fiction adventure Total Recall, I had only vague memories of seeing it on opening night. I mean, I remembered that I hated it, but I wasn’t sure why. I was already a Paul Verhoeven fan based on RoboCop, though I didn’t know anything else about his work. I know I was put off by the scene where Arnold Schwarzenegger puts a bullet in a woman’s head and then yuks it up with one of his trademark murder jokes. Sure, the screenplay has taken pains to establish the character’s unforgivable duplicity, but that’s the problem: She’s disposable, and she’s a punchline. (No wonder Sharon Stone jumped at the chance to play a serial murderer of men in Verhoeven’s next film.) And I recall that I was annoyed beyond reason by the film’s climax, which involves a very sudden change to the environment on Mars. The science behind it struck me as insultingly preposterous. Still, I think what I really objected to, what actually offended me, was the light tone. After RoboCop, which struck me as an appropriately sick joke about fascist tendencies in American law enforcement (still in the news!), I guess I expected Verhoeven to treat Philip K. Dick’s epochal ruminations on human consciousness, thought, and identity with some gravity (cf. the similarly Dick-inspired Blade Runner) instead of turning them into a wildly overblown comic-book complete with an absurdly-ripped muscleman as the self-doubting superhero at the centre of the action. That’s on me; Looking back on Total Recall after three decades, I can see it more clearly. For Verhoeven, the cartoonishness is the point.

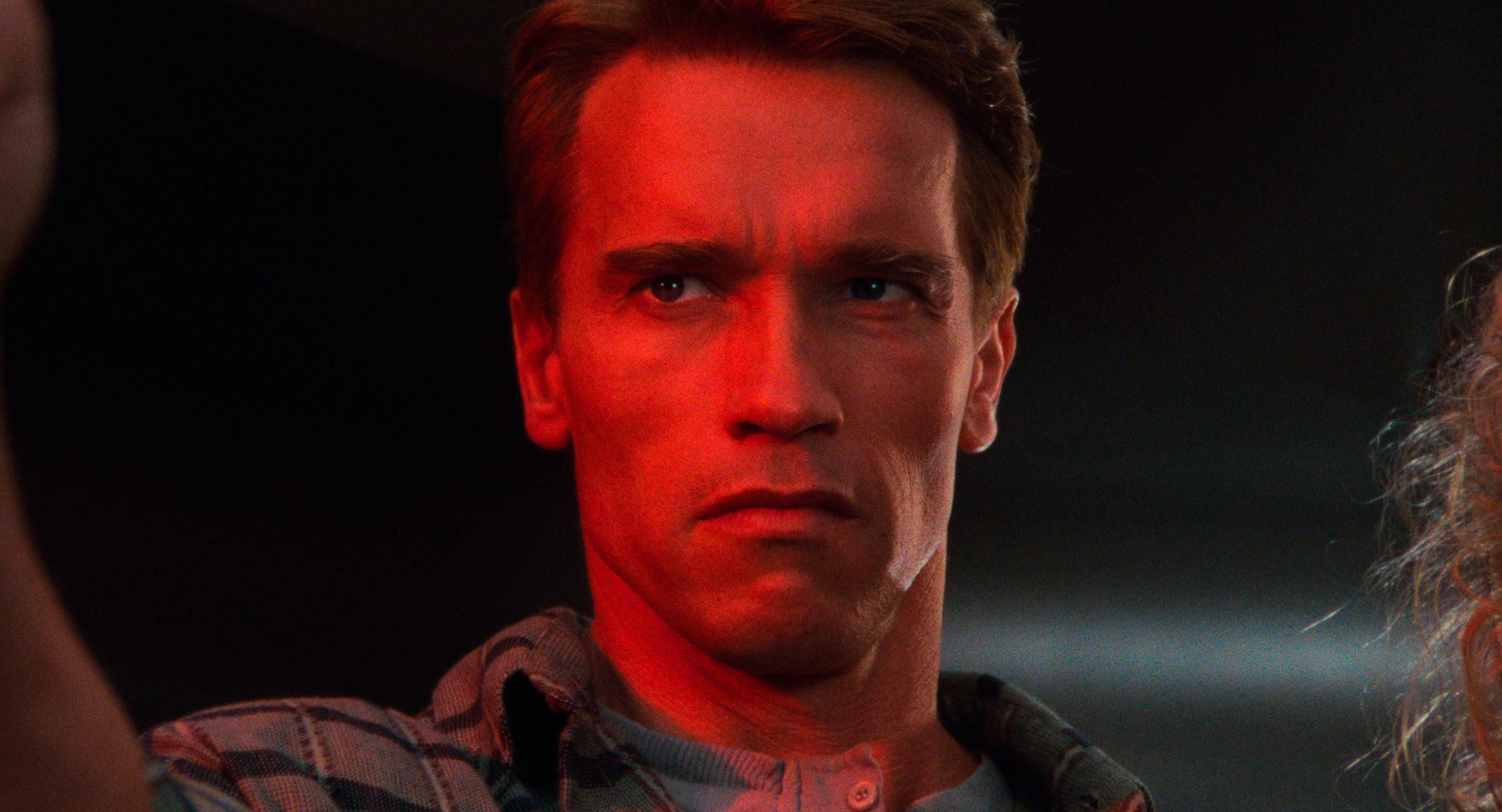

Look at it this way: it’s easy to read Verhoeven’s English-language output through the 1990s as a series of sardonic commentaries on American media. If RoboCop was a satire on cop movies, then Basic Instinct is a satire on police procedurals and Starship Troopers is a satire on military propaganda and Showgirls is a satire on, well, show business. That makes Total Recall, I guess, a satire on high-concept Hollywood action movies. Everything about it is vulgar, starting with the wildly inapposite casting of Schwarzenegger as our figurative everyman. The premise of the film is that an ordinary Joe’s world is turned upside-down when he learns that his entire life may be phony-that it could be the product of false memories implanted to obscure his former career as a planet-hopping secret agent with a Martian agenda. Dick’s protagonist was a government clerk-a “plain, dull” person who belatedly realizes he’s not plain or dull at all. Schwarzenegger was great as Conan and the Terminator, iconic killers you can see coming from a mile away. But how plain or dull is a perfectly sculpted Übermensch with biceps the size of toaster ovens? The whole concept of a secret identity falls apart if Clark Kent just looks like Superman in street clothes.

Does that matter, ultimately, when you’re making a summer blockbuster? David Cronenberg, one of a string of directors who had been attached to the Total Recall adaptation by Alien scribes Ron Shusett and Dan O’Bannon, must have felt the project being tugged this way when he worked on it back in 1984, first with William Hurt and later with Richard Dreyfuss expected to star. As Cronenberg tells the story, Shusett was interested less in Philip Dick than in “Raiders of the Lost Ark Go to Mars.” Producer Dino De Laurentiis stuck with the property until his DEG Studios went bankrupt, just as a Bruce Beresford version starring Patrick Swayze was getting off the ground. (By that time, even O’Bannon had abandoned the project.) It was reanimated when Schwarzenegger (who had sought the lead role for years) got Carolco to buy the rights and approached Verhoeven with what I have to imagine was an offer he couldn’t refuse. So give Arnold his due: whatever Total Recall is-part metaphysical science-fiction yarn, part colorful-but-dopey fantasy adventure-Schwarzenegger is as responsible as anyone for how it eventually turned out.

So Schwarzenegger plays Douglas Quaid, a construction worker who dreams of starting a new life on Mars, home to a near-future mining settlement riven by a civilian uprising against the corrupt ruling authority, led by the dictatorial Cohaagen (Ronny Cox). Frustrated by a thwarted desire “to do something with my life…to be somebody,” Quaid visits Rekall, a company that promises to implant memories that will make Quaid believe he has visited Mars without ever leaving planet Earth. The procedure goes awry, however, with Quaid suffering a “schizoid embolism.” As it turns out, Quaid has already had his memory wiped clean in order to eliminate evidence of his previous life as Hauser, an intelligence officer for the Martian government, in the form of memories that Rekall accidentally resurfaced. The revelation leaves Quaid confused but turns his life into the adventure he craved; he recovers a video recording left behind by his former self, who reveals that he turned against his employers and has designs on bringing down Cohaagen. Agent Hauser urges Quaid to hop on the next flight to Mars and await further instructions.

Verhoeven’s direction is resolutely over-the-top from the very first scene, a dream where Quaid imagines himself gasping for air on the Martian sandscape after accidentally shattering the glass of his face helmet. Verhoeven pushes in for an extreme close-up of Quaid’s face (in actuality a Rob Bottin puppet) as his eyes and tongue bulge painfully out of his head. The effect is almost too garish to be believed, but it turns out to be entirely in keeping with the overall tone of the film. There’s a security checkpoint with a full-body scanner that displays patrons’ skeletons at life-size. There’s a red-light district on Mars called Venusville, which Verhoeven based on Amsterdam’s red-light district and is home to a three-breasted hooker. There’s a resistance leader named George whose brother, Kuato, is in charge of the rebellion and is also embedded in George’s abdomen. (Citing Brian J. Robb’s Counterfeit Worlds: Philip K. Dick on Film, the film’s Wikipedia entry claims Kuato originated in one of David Cronenberg’s script drafts, though Shusett insists in Rob van Scheers’s Paul Verhoeven that he dreamed up Kuato after looking at pictures of conjoined twins.) Most notoriously, Verhoeven stages a scene where Quaid grabs a random bystander to use as a human shield against machine-gun fire.

Typically for Verhoeven, the results were too much for the Hollywood ratings board, which returned the film with the same X rating that graced his original cut of RoboCop, necessitating minor edits throughout before it could be delivered to theatres with an R. While RoboCop‘s excesses seem to shine a light on an American pathology, Total Recall‘s mayhem feels more purely indulgent-unless you think Verhoeven sees Quaid’s eagerness to adopt the trappings of a secret agent man, including his stone willingness to sacrifice others to save his own skin, as a symptom of pride, selfishness, and self-aggrandizement in the American psyche.

Too much? The screenplay is at least more clever than I realized back in 1990. The scene in which Quaid begins to realize that his life has suddenly become bigger than he ever imagined isn’t just an exposition dump that sets up the film’s remaining two acts-it’s a purely visual expression of Quaid’s feelings of inadequacy. As he watches the video presentation left for him by his alter-ego, Hauser (whom Schwarzenegger plays as a more confident, more charismatic, and more consequential version of Quaid), you can see Quaid marvelling at the man he once was and hopes he could become again. It’s no wonder he rushes to the Red Planet without worrying too much about what kind of trouble awaits him. It’s not just a chance to begin again; it’s an opportunity to realize the sort of fantasy Quaid has long nurtured for himself. Later in the film, a Rekall executive (Roy Brocksmith) shows up to inform Quaid that he has suffered that “schizoid embolism.” The exec says he has been injected into Quaid’s dream in a rescue mission, and warns that if he doesn’t snap out of his fantasy, Quaid will be stuck in “permanent psychosis” with his mind destroyed. What to do?

Total Recall is loud and gaudy, but Quaid’s situation is more poignant than the film at first seems to acknowledge. If Rekall’s fake experiences are as convincing as they’re reputed to be, then Quaid has no way of knowing whether the man is telling the truth. He has to interpret his perceived reality in one of two ways: he may be a double agent helping facilitate a righteous insurrection against an oppressive government; or he may be a sad body-builder with a dead-end construction job and an increasingly tenuous connection to sound mental health. The film doesn’t dwell on this point, but what Quaid’s offered is a false choice. It’s true that clues sprinkled throughout suggest that Rekall may well be telling Quaid the truth about his condition. (For one thing, the folks at Rekall seem to know exactly how Quaid’s Martian excursion is fated to unfold, supporting the idea that it’s a pre-scripted experience; for another, the film culminates in a happy ending with a fade to white, which seems deliberately suggestive in a way the expected fade to black wouldn’t.) Yet it seems clear that Quaid would experience a return to his former life as a spiritual defeat too dispiriting to contemplate-and what kind of movie would that be, anyway? While you could read this thirst for elevated sensation as a metaphor for moviegoing, to me, the existential implications are deeper. In the end, it’s like this: whether Quaid believes in himself or not, he has to believe in himself. That’s a profound observation, since it’s the same impulse that helps us get out of bed in the morning, however discouraging our circumstances may be. As Quaid himself puts it: “If I’m not me, then who the hell am I?”

THE 4K UHD DISC

StudioCanal returned to the original 35mm negative to create a new 4K master of Total Recall, a project that must have presented a special kind of challenge. The problem isn’t so much the film’s age as it is the era of its special-effects work. Many of its shots don’t involve special effects at all, of course, and of those that do, some of them were captured in-camera. Optical process shots nevertheless present an issue, as they’re at least one generation removed from the original camera negative in quality. That means they appear softer, with less dynamic range, a difference that should be glaringly apparent in a UHD and HDR presentation. The trick is to match the process shots as closely as possible to the camera-original material for the sake of consistency-without degrading the overall presentation. StudioCanal has managed that pretty well, as hue and saturation remain very consistent from shot to shot, despite the unavoidable shifts in picture grain and contrast.

Colors are exceptionally saturated-almost too saturated (the hot pink of Sharon Stone’s workout top is almost too intense to gaze upon directly), with skin tones sometimes tending towards the beet-red. (Those are deliberate creative decisions, of course, and Lionsgate assures that Verhoeven himself supervised this new “restoration.”) More troublesome to my eyes is the interaction between the pin-sharp film grain and the Dolby Vision color grade, which sometimes adds harshness to what should be an organic grain structure, especially in scenes with neon bulbs or other specular highlights. I don’t know how, exactly, you deal with this problem-I suspect the best solution will involve more carefully managing the HDR grade rather than simply cranking up the noise reduction-but I hope studios figure it out. I wish it had been possible to restore the edited bits of gore for an unrated release, but this new version is a definitive visual take on Total Recall.

Audio quality is fine if unexceptional. Though Total Recall doesn’t have the busiest sound mix in action cinema, there are plenty of directional audio effects across the front horizontal soundstage, along with occasional detours into the height channels (especially during the third act on Mars), and Goldsmith’s score sounds terrific in Dolby Atmos, with the musical orchestration, at least, taking advantage of the surround channels. Low-frequency effects are deployed sparingly but forcefully. Basically, the sound is wholly appropriate for the film’s vintage-remember, Total Recall was released on the cusp of the 1990s heyday of digital sound formats, just before sound designers were emboldened to create ever-more-active surround mixes.

The 30th-anniversary package offers one UHD BD, two BDs (one dedicated to special features), and a digital download code. Three new-to-this-release features are included on both the UHD and BD platters. “Total Excess: How Carolco Changed Hollywood” (59 mins., 1080p) purports to tell the story of Andrew G. Vajna and Mario Kassar’s mini-major studio, which grew to prominence with the release of Sylvester Stallone’s Rambo movies in the 1980s, plateaued on the back of hits like Total Recall, Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), and Basic Instinct (1992), and then collapsed under the weight of the expensive failures of Showgirls and Cutthroat Island (both 1995). Unfortunately, neither Vajna (who died in 2019) nor Kassar (who presumably declined to be interviewed) appear on screen, though a number of their associates and creative collaborators show up, such as Verhoeven, Michael Douglas, Oliver Stone, editors Mark Goldblatt and Mark Helfrich, and film music producer Robert Townson. (Alan Parker, George Cosmatos, and Walter Hill appear in archival interview footage.) It’s entertaining enough, thanks to lots of footage from the films under discussion, but it feels more like an extended clip reel than any kind of definitive history.

“Open Your Mind: Scoring Total Recall” (21 mins., 1080p) foregrounds a discussion of Jerry Goldsmith’s score by a slate of interviewees including film music devotees Daniel Schweiger, Jeff Bond, and Lukas Kendall, as well as Townson again. Among the elements of Goldsmith’s work foregrounded here are his combination of orchestral and electronic instruments, his use of brass to underscore the frustration and anger of Michael Ironside’s character, and the difficulty orchestras ran into when it came time to play the complex music Goldsmith had composed. (Apparently the experience soured him on action films.) There’s also some talk about the similarity between Goldsmith’s compositions here and Basil Poledouris’s bombastic, percussive score for Conan the Barbarian, the suggestion being that Goldsmith may have been asked to emulate temp tracks from Conan.

“Dreamers Within the Dream: Developing Total Recall” (8 mins., 1080p) presents an audio-only interview with concept artist Ron Miller accompanied by an assortment of his illustrations for the film. He discusses the challenge of creating designs that are both scientifically plausible and visually interesting, but also takes a longer view of the project as a whole, recalling his year-long engagement with Cronenberg’s version of the film and talking about changes made after Schwarzenegger became the lead. Last (and least) among the new-for-UHD special features is a newly-created 30th-anniversary trailer (1:33) for StudioCanal’s remastered version of the film.

Holdovers from Artisan’s 2001 DVD special edition include an audio commentary with Verhoeven and Schwarzenegger, present on both BD and UHD. It zips along at a pretty good clip, although it’s not exactly bursting with information; Verhoeven and Schwarzenegger spend a lot of their time simply verbalizing what’s happening on screen and drawing attention to every ambiguous story beat that suggests Quaid may be living in a dream. In Schwarzenegger’s telling, he helped broker a quick-turnaround deal between De Laurentiis and Carolco once the former’s studio went out of business and then immediately met with Verhoeven about directing. Verhoeven explains that the bleak, bare-concrete style of many of the sets was based on the Brutalist architecture found on filming locations in Mexico City. He also reveals that the scene where the Rekall executive tries to convince Quaid that he’s still dreaming was inspired by Alfred Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain. After watching Michael Ironside shoot a woman in the back, Schwarzenegger chuckles at Verhoeven’s excess: “I love it. It’s one thing to shoot somebody. It’s another thing to shoot them in the back. And it’s another thing to shoot a woman in the back.”

Three more features are exclusive to the second BD. “Imagining Total Recall” (30 mins., 480p), also from the 2001 DVD, holds up surprisingly well. It’s the most comprehensive making-of feature in the package, combining EPK-style soundbites and B-roll from the production with latter-day cast and crew interviews. Shusett details the film’s long history in development, production designer William Sandell remembers nearly the entire crew getting sick in Mexico City, and VFX supervisor Eric Brevig and CGI director Tim McGovern describe the intricate and groundbreaking VFX, encompassing a ton of Martian miniature work and one of the first appearances of CG in a feature film. Arnold bitches about Carolco’s failure to promote the film aggressively until he leaned on the studio, and even Jerry Goldsmith shows up to describe his “fairly avant-garde, very difficult” score-and to answer critics who claimed it lacked a theme.

“Models & Skeletons: The Special Effects of Total Recall” (23 mins., 1080p), a Studiocanal production from 2010, documents some of the film’s key special effects scenes by way of interviews with Mark Stetson, who remembers renting a 20,000-square-foot warehouse for his company, Stetson Visual Services, to construct miniatures for the film, and Tim McGovern, the CGI Director at Metrolight Studios, creators of the X-ray skeletons at the security checkpoint. Stetson tells how various effects shots were designed and executed, highlighting the use of imagery front- and rear-projected (in one case using a miniature projector originally developed for The Abyss) onto tiny screens built into the miniatures themselves. He remembers some fears that the deep reds of the Martian landscape would bleed and bloom on VHS tapes but says Verhoeven was unbothered: “Paul said quite emphatically that he didn’t care about the video aftermarket.” McGovern goes into even more detail about the skeleton sequence, which was bedevilled by problems technical and otherwise before finally appearing flawless in the finished film. “We didn’t know to negotiate properly for screen credits,” he laments, noting that his name appears in the credits only on VHS versions of the film, and even then only because McGovern earned a Special Achievement Academy Award for his work, shaming Total Recall‘s producers into making amends. (No, his name isn’t in the credits on the UHD BD, either.) Finally, “The Making of Total Recall” (8 mins., 480p) is disposable vintage EPK fodder from 1990 aimed at interested but unconvinced moviegoers. It’s notable only for its brief comments from Verhoeven, Brevig, Ironside, Cox, Schwarzenegger, and the elusive Rob Bottin.

113 minutes; R; UHD: 1.85:1 (2160p/MPEG-H), Dolby Vision/HDR10, BD: 1.85:1 (1080p/MPEG-4); English Dolby Atmos (Dolby TrueHD 7.1 core), English DTS 2.0, French 5.1 DTS-HD MA, Spanish DTS 2.0; English SDH, French, Spanish subtitles; BD-100 + BD-50 + BD-25; UHD BD: Region-free, BD: Region A; Lionsgate