In his engaging biography of Woody Allen, Eric Lax recalls Tennessee

Williams’ famous response to a reporter who asked him to define

happiness: “Insensitivity, I guess.”

Deep Focus | Movie Reviews for the Internet

"Since 1994"

In his engaging biography of Woody Allen, Eric Lax recalls Tennessee

Williams’ famous response to a reporter who asked him to define

happiness: “Insensitivity, I guess.”

More than a few single eyebrows have been raised at Antz, the debut animated feature from Dreamworks SKG. For one thing, the movie features the voice talents of neurotic New Yorker Woody Allen, not exactly a big name in children’s entertainment. For another, the language is a little more reckless than you’d expect from a kiddie pic, with Allen’s neurotic insect shtick even alluding to his, ahem, “erotic fantasies.” And finally, the film’s last reel turns on a weird ants-in-peril Holocaust scenario that’s likely to sail over the heads of children who don’t get the reference.

All of those concerns spring, of course, from the unavoidable perception that animated movies are, by definition as well as design, aimed solely at children. Adults who enjoy animated Disney features, for instance, generally take a sort of pride in their appreciation of cartoons, as though it’s some indicator that they still haven’t lost touch with their inner children. At least that’s the perception that holds sway in the U.S. — I suspect that in Japan, where animated feature films are often more cerebral and punishing than their live action equivalents, there would be no such confusion about the intentions of the makers of Antz.

This is the project that was raced through production at computer graphics house Pacific Data Incorporated in order to beat A Bug’s Life — Disney and Pixar’s follow-up to the immensely successful Toy Story — to movie screens. Toy Story is itself kind of a cartoon for adults, with its wry subtext about the commercialization of children’s fantasy adventures running beneath a more earnest story about friendship and self-esteem. The postmodern jokes are there, if you care to get them. And if not, Toy Story is still one beauty of a children’s flick.

Antz is a lot like Toy Story in many respects, although it’s not quite as skillful. The surface story is about a meek worker ant (Allen) named Z — rather, he’s named Z-4195, the anonymity of which is part of his problem: “When you’re the middle child in a family of five million, you don’t get any attention.” There’s no self-determination in the ant colony, where millions of ant larvae are deemed either workers or soldiers and then shoved off for training in whichever profession matches their destiny.

Even the royal family is expected to play by the rules — princesss Bala (Sharon Stone), through no fault of her own, is betrothed to the megalomaniacal General Mandible (Gene Hackman). One night, she sneaks out to a bar with the intention of asking a common worker ant to dance, for kicks. That ant happens to be Z, who impresses her — just barely — with a knack for individuation before they’re separated by a nasty melee. But Z is determined to catch her eye again and hatches a scheme to masquerade as a soldier in order to get close to Bala. Everything goes wrong, and Z finds himself sent to war against a nearby colony of termites. After traversing a number of plot points worthy of a historical romance pic from the 1930s, Z manages to win Bala’s heart, but finds out that Mandible has a sinister plan for subjugating the colony to his own rule.

Along the way, the plot is peppered with jokes about subverting the social order and eye-popping computer animation involving underground vistas swarming with tiny computer generated ants. The animation is impressive; it’s also a little distracting in the way it calls attention to itself. Look at the faces of the antz themselves, which are sleek, fully articulated representations of the corresponding human versions. The problem is that, while PDI can make them do the darnedest things, they don’t have naturalism down. The characters’ movements are exaggerated and artifical, like they were being controlled by puppeteers. Contrast these sleek new models with the subtly expressive faces of old-fashioned animation, and you’ll see there’s clearly a lot of ground to be convered before the computer-generated model is as affecting as the hand-drawn image. (By design, the playthings in Pixar’s Toy Story are supposed to have smooth, mostly featureless mugs, which dovetails well with the qualities of computer animation.) Finally, in the context of a wholly created world, the product placements (for Pepsi and Reebok) are even more disconcerting than usual.

Antz could also stand a little more inventiveness. For the most part, the action scenes are the sort of stuff that mega-budget Hollywood blockbusters would stage if they had the time and money to go the distance. Too many of the visuals here are reminiscent of mind-blowers we’ve already seen in live-action movies, from the outrageous cliffhangers of an Indiana Jones movie to the bug attacks in Starship Troopers and the post-assault sandscape of Saving Private Ryan‘s Omaha Beach. And for Z, the hero’s journey basically consists of being in the right place at the right time.

What really works is the dialogue, which is fast and funny and helps carry the action through the slow spots. (I’d be very surprised to hear that Allen didn’t have a hand in tweaking his trademark one-liners to suit Z, a more agreeable portrayal of the typical Woody character.) In a way, that’s faint praise for animation, a medium that’s arguably at its best if you don’t need dialogue to understand what’s going on. If it’s not entirely successful, Antz is at least unique — in terms of casting, dialogue, and subject matter, it’s the first Hollywood animation in years that isn’t 100 percent calculated to be kid-friendly.

Directed by Eric Darnell and Tim Johnson

Written by Todd Alcott, Chris Weitz and Paul Weitz

Production Design by John Bell

Edited by Stan Webb

Starring Woody Allen, Sharon Stone, Sylvester Stallone, and Gene Hackman

Theatrical aspect ratio: 1.85:1

USA, 1998

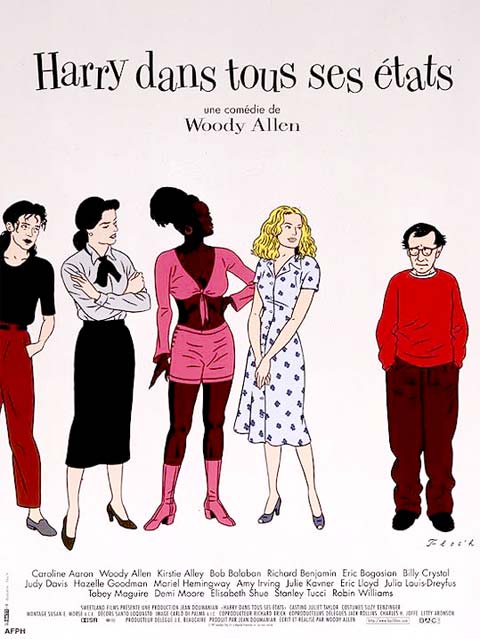

At a point in his career where Hannah and Her Sisters and Radio Days are his “earlier, funny films,” Woody Allen has finally managed to start making Woody Allen movies again.

These days, seeing the new Woody Allen film is a little like spending some time with an old lover. Things just haven’t worked out. Those once-charming quirks and peccadillos have grown into irritating mannerisms, and while you can’t put your finger on what’s missing, it just seems like the magic is gone. You get the feeling that the two of you have nothing left in common. But when your ex makes unexpected overtures toward seduction (say, by announcing that his new film will be a musical comedy) you’re intrigued. Stumbling toward your rendezvous, you’re shot through with anticipation as well as the fear that you’ll only be let down once again — how do you get yourself into these things, anyway?