SPOILER WARNING IN EFFECT. In some sense, Shivers, a venereal horror movie that invites you to track the vectors of sexual intercourse among a group of apartment-dwellers, is a parody of a soap opera where the point is who is sleeping with whom. It’s also a spit-take on those sex-ed hygiene films that try to frighten teenagers into abstinence. Set almost entirely in a Montréal apartment complex and photographed in a jaundiced palette that leans towards yellow-green, it’s about the proliferation of parasites that make their way from body to body by a variety of sickening means, transforming their hosts into insatiable sex maniacs. Shivers was Cronenberg’s first commercial feature, and by the director’s own admission he was hardly equipped at the time to head up a production with any significant budget. And yet it’s some kind of masterpiece. If it’s a naive film in some respects, it benefits from naivete. The hurried, sometimes awkward mise en scène may as well be deliberate, given that it jibes so well with the film’s chilly, alienating tone. Any cut corners in lighting, design, and special-effects work only enhance the generally grody feel. And there’s a lot that’s grody about Shivers. That’s why it works so well as a chilling overture to a filmmaking career that critics have described as The Cronenberg Project, one in which the director uses film after film to explore love, sex, physical transformation, and mortality.

Certainly, Shivers is Cronenberg’s sleaziest film. As the director himself put it in the Faber & Faber volume Cronenberg on Cronenberg: “Critics often think I’m disapproving of every possible kind of sex. Not at all. With Shivers I’m a venereal disease having the greatest time of my life and encouraging everybody to get into it.” Is he kidding? Well, yes and no. It’s true that there is something devilish and knowing about Cronenberg’s shotgun marriage of the low-budget monster movie and the low-impact skin flick. But even though the denizens of Starliner Towers, the mixed-use real-estate development where the film is set, are among the most boring protagonists in 1970s horror cinema, Shivers doesn’t pretend that sex, all sex, is good, clean fun. The movie’s monster is the creation of a mad doctor who implanted it in a teenager he had been grooming for some time, an unsavory scheme with unplanned consequences, as the newly promiscuous woman became a super-spreader for the parasitic disease. At first, those infected notice only strange shapes under their skin, accompanied by feelings of unease. As the disease progresses, the critters’ hosts become bolder, venturing out of their now-boring bedrooms into the building’s common areas to find new partners, expelling heat-seeking, penis-like slugs along the way. Rape is explicitly on the agenda, as are incest and pedophilia, which are suggested in brief, unsettling vignettes. You could ask: is sexual abuse still abuse if the victim has been biologically altered to enjoy it? Well, as a tool designed specifically to strip people of their agency, the Shivers monster is immoral.

Cronenberg doesn’t dwell at any length on these concerns, though. Shivers unfolds in a series of abruptly alternating standalone episodes, the purpose of toggling between them partly just to propel the film forward during some slow patches. So we cut away, repeatedly, from Dr. Hobbes (Fred Doederlein) strangling, stripping, and scalpel-ing Annabelle (Cathy Graham) to watch Nicholas Tudor (Alan Migicovsky) clean his teeth and see the property manager (Ronald Mlodzik) introduce a young couple to the building’s amenities. Even the big centerpiece sequence in which a parasite sneaks into the tub where Betts (genre legend Barbara Steele) is bathing and swims up, singlemindedly, into the space between her thighs, is broken up: We see her start the water for her bath before Cronenberg cuts away, not returning to her tub for more than four full minutes. It all makes Shivers a bit of a disorienting experience; the fragmented assembly is a little hard to get a grip on in one viewing.

Cronenberg dramatizes most of it in the affectless manner that would become a defining (and enabling, on a budgetary level) style of his early work. The performances are mostly stiff and restrained, which could be blamed on mediocre acting, but I think they must be at least somewhat directed that way. While I love the early films, emotional depth wasn’t really a Cronenberg specialty until he started working with actors of the calibre of Christopher Walken (on The Dead Zone), Jeff Goldblum and Geena Davis (both on The Fly), and Jeremy Irons (Dead Ringers). The accelerated shooting schedule didn’t allow time to shoot much coverage, so the action was captured with a minimum of set-ups, and the lighting and camerawork are plain. Sound is important, despite Cronenberg’s use of library music for the film’s score. The sonic backdrop here includes classic horror-movie stings, with strings and percussion and kerplink-kerplunk keyboard atonality, but also a growling drone that increases in volume along with the intensity of the action, augmented by some successfully sickening foley effects. The overall effect is alienating; Shivers does feel almost like the parasites themselves could have directed it.

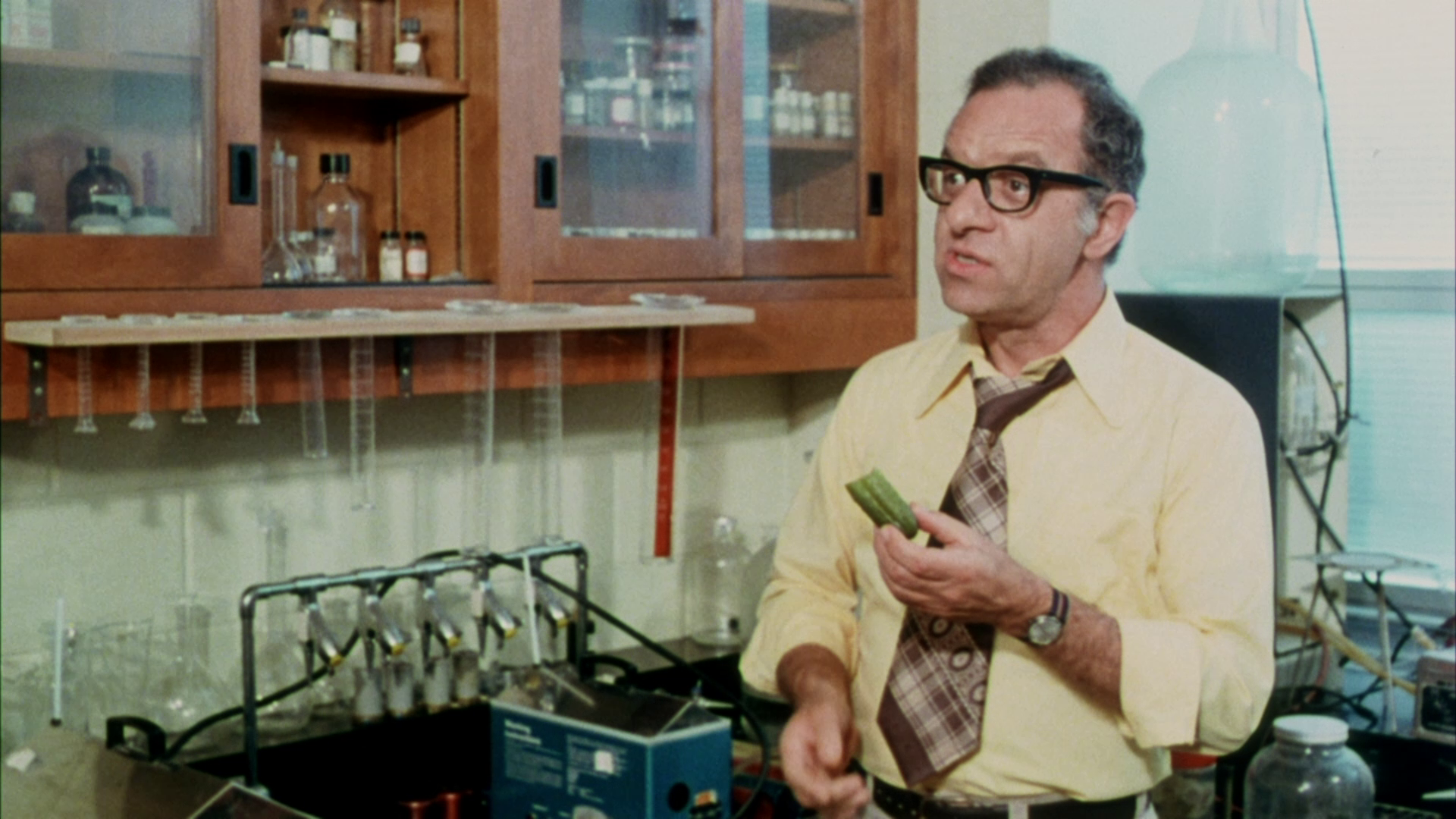

But Shivers has a sense of humor. As evidenced by Cronenberg’s jovial claim that it has a happy ending if you’re rooting for the parasites, it is self-consciously aware of the type of movie it is. It’s not camp, exactly, but when an older resident (Nora Johnson) lunges from her apartment to drag a passerby into her fantasy, she declares, “I’m hungry…hungry for love” in a knowing riff on a Boris Karloff monster-grunt and/or a George Romero zombie that wouldn’t be out of place in a John Waters film. I love the scene where Dr. Hobbes’s associate, the pickle-munching Rollo Linsky (Joe Silver, in a performance straight out of a 1970s TV police procedural), rings up Dr. St. Luc (Paul Hampton) to explain what Hobbes was up to and, more crucially, what his philosophy was. Cronenberg dares the viewer to pay attention to his exposition dump, given that the screen is full of an annoyed-looking Lynn Lowry, who is the nurse undressing in a bid to distract the doctor from his call.

Lowry is something special, by the way. Steele may be the genre pro in residence, but Lowry has a unique, otherworldly look that makes it hard to take your eyes off her. Cronenberg gives her character, Forsythe, a crucial, creepy monologue near the end of the film in which she describes her dream of making love with a dying man, who tells her that “everything is sexual, that disease is the love of two alien kinds of creatures for each other.” She becomes convinced in her dream that “even dying is an act of eroticism,” maybe a recasting of Georges Bataille’s Nietzscheanist line that “eroticism is assenting to life even in death.” She leans closer and closer to the doctor, her fervor increasing until she attempts to pass a parasite from her mouth to his, and he slugs her. This, too, is funny, in its way-his very physical rejoinder shuts down her philosophical assertion, and his next act is to cover her mouth with a piece of tape, as if to keep her quiet, although of course he is trying to ensure that more parasites won’t spill out of her.

Nurse Forsythe eventually gets the last laugh. As another Cronenberg character would later put it, she has become dangerous because she now has something Dr. St. Luc does not: a philosophy. That’s another way to look at Shivers. As the building’s tenants are turned, one by one, they don’t behave like victims. Instead, they seem to become emboldened and empowered-newly confident and assertive. They present to some degree as self-styled visionaries, eager to recruit true believers. And that’s where the line blurs: Shivers is a science-fiction horror movie about a disease spread by a parasitic monster, but it sometimes feels like it’s about cultists in the same way that some vampire movies feel like they’re about cultists. Nobody wants to be attacked in the dead of night and have their blood drained by a grim creeper with a Hungarian accent, though once bitten, the victims mostly agree that it’s cool to be a vampire.

Then again, Cronenberg might have come close to giving away the game in a 2000 Critical Quarterly interview with Adam Simon. He compares the film’s climactic moment-in which Nurse Forsythe finally presses her open mouth against the doctor’s face, allowing the parasite to enter him-to “the concept of losing one’s virginity, that you are no longer innocent, the Catholic view.” Maybe Starliner Towers, in all its grey repressiveness, is Cronenberg’s peculiar inversion of the Edenic ideal, with Dr. St. Luc filling the role of a boring-as-hell Adam who has to be wrestled by Eve into accepting the so-very-delicious apple she plans to shove down his throat. This Biblical reading of Shivers subverts scripture one last time: Adam and Eve were ashamed as they were cast from the garden, but the infected pour out of the Starliner Towers parking garage in a long line of cars, driving towards the city and looking for a good time. Just as God tempted innocence with abandon and saw innocence lose the fight, Shivers pits the squares against the party people, and the party people come out on top. There’s something genuinely transgressive, even by Cronenberg’s standards, about that image: all those horny monsters in human skin lighting out for the city, the cheesy, unpretentious grins on their faces signaling a celebration of their new flesh.

THE BLU-RAY DISC

Shivers made its Blu-ray debut on a 2014 Region B release from Arrow Video. The new disc in Lionsgate’s Vestron Video Collector’s Series seems to have used the same video master, albeit with the compression cranked way up. Arrow’s transfer had an average bitrate of around 35 Mbps, which Vestron slashes to just 26 Mbps. The difference is most evident in the grain structure, often looser and muddier on the Vestron release. (It’s not clear why Vestron got so stingy with the bits when there is plenty of space left on the BD-50 platter.) The first pressing of Arrow Video’s disc, taken from a recently-minted Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) restoration, included a censored version of the film, an embarrassing error that was corrected in subsequent editions; Vestron’s disc contains the correct, unedited version. Anyway, the TIFF color grade appears to be identical across both versions, except where the comparative smoothness of the grain on the Vestron release shifts the perceived color ever so slightly. It’s a pretty finely detailed grade, pushing the overall palette towards a queasy yellow-green pallor while keeping skin tones mostly accurate and realistic, but dynamics have been limited, with a lot of detail that was clearly visible on the 1998 Image Entertainment DVD crushed into inky black shadows. There is a bit of flicker in the darkness of a few scenes, too.

While this is presumably Cronenberg’s preferred look, since he’s said to have supervised and approved the 2013 TIFF remaster, on the new audio commentary featured herein he claims not to have watched Shivers in “decades,” so who knows? At any rate, Vestron’s monaural 2.0 DTS-HD MA track is notably superior to the Arrow version, whose loud and muffled sound is probably due to attempts to use low-pass filters and dialogue normalization to reduce the audibility of background noise. Vestron’s track sports lots of varying ambient room sound from the original dialogue tracks, which I suppose can be distracting, especially if you’re listening closely with headphones. Still, the overall quality is brighter, with broader dynamics, and the music cues, especially, play out on the Vestron disc with substantially more detail and definition. A voucher for a digital copy is slipped into the box, so you can have Shivers with you any time.

Chief among the special features are two new audio commentaries moderated by writer-filmmaker (and former Fangoria editor) Chris Alexander, one with Cronenberg and the other with co-producer and production manager Don Carmody. The Cronenberg yakker will be of special interest to fans, naturally, and newbies to Cronenberg and/or Shivers should find it particularly informative. Cronenberg talks about landing his first job directing a commercial project and, in the process, recounts some of the history of the Cinépix production company founded by his mentor, John Dunning, and André Link, which got its start selling softcore sex films into European markets. (Fun fact: in 1998, Cinépix changed hands and was renamed “Lions Gate Films.”) Among the less well-trod paths Alexander leads him down are a discussion of his experiences acting in other people’s films and an ode to les Fournier Frères, the old-school stuntmen who oversaw the automobile action that takes place in the garage underneath Starliner Towers. I was a little surprised to hear that Cronenberg apparently still has a grudge against the late Dan O’Bannon, whom he has accused repeatedly of stealing the reproductive parasite concept from Shivers for use in Alien. He’s fairly good-humored about it, but it’s an axe he’s been grinding for decades. “The evidence is circumstantial, but it’s evidence,” he says. Alexander’s conversation with Carmody covers too much of the same ground, although he delivers some amusing anecdotes. Explaining how smoke was generated on set in scenes where a Shivers slug was supposedly eating into a human body, he remembers pouring titanium tetrachloride directly on Joe Silver’s skin. “It was a terrible idea,” Carmody says. Then, he adds, “We pulled that same trick in Rabid on an actor. He ended up suing us.”

HD video featurettes include “Mind Over Matter with Writer/Director David Cronenberg” (12 mins.), in which the director again tells the story of how he hooked up with Cinépix, and we see glimpses of a shooting draft of the Shivers script. Cronenberg remembers the Canadian government taking grief for partially financing the project when a writer for Saturday Night attacked the film under the headline “You Should Know How Bad This Movie Is: You Paid for It,” but notes that Shivers made more than enough money to return the government’s investment. In the engaging “Outside and Within with Special Make-Up and Creature Effects Creator Joe Blasco” (13 mins.), Blasco says he agreed to work with the then-unknown Cronenberg solely on the strength of Barbara Steele’s name on the cast list. He insisted on doing her make-up as well as the effects work, fulfilling a long-standing dream: “All this other stuff was gingerbread, as far as I was concerned.” Blasco does make the eye-opening claim that he directed the special-effects scenes himself, explaining that Cronenberg “was welcoming any help he could get.” Near the end of the segment, he pulls out one of the actual creatures used on the film and muses, “I think it looks more like a penis than a turd.”

“Celebrating Cinépix: The Legacy of John Dunning” (10 mins.) is a loving encomium to the studio’s co-founder, built entirely around an interview with his son Greg. The younger Dunning says his father probably could have retired from the business on the earnings from their 1969 hit export Valérie, but instead pumped his profits back into film production. Among the special interests of Cinépix were movies with female protagonists, Dunning says, citing Ilsa, the notorious “she-wolf of the SS,” as an example. He also reveals that his father, disappointed by the quality level of the kills in the 2009 My Bloody Valentine remake, had been hoping to produce a sequel to that film when he died in 2011. John Dunning himself speaks in a vintage audio interview that plays alongside the disc’s Still Gallery (9 mins.), discussing his career during the early years of Cinépix. “If I pioneered anything,” he says, “It was to break the censorship in Québéc.” And he, too, remembers the Ilsa series fondly: “She sold around the world. She became an icon.” The gallery itself features a so-so array of production stills highlighted by a nifty collection of international key art and video boxes.

The last major extra is an archival Cronenberg interview from 1998 (21 mins., upconverted from SD to 1080p), a holdover from the Image DVD. It’s a slightly different perspective on Shivers from a somewhat younger Cronenberg, touching on everything from pre-production to the film’s release and legacy, but it generally repeats stories already conveyed elsewhere on this disc. He does add some detail to Carmody’s titanium tetrachloride anecdote, remembering his phone call to producer Ivan Reitman: “Ivan, the actor is vomiting in the hall…. No, it’s not part of the scene. I think he might have to go to the hospital. I’m not sure.” In the end, Silver did not go to the hospital. He finished vomiting, Cronenberg says, and then shot the scene. Two versions of the same 90-second theatrical trailer (a poor-quality, overly noise-reduced HD transfer promoting the film as Shivers and a much nicer version selling it under the alternate title They Came from Within), a single one-minute TV spot for They Came from Within, and a series of three radio spots complete this edition.