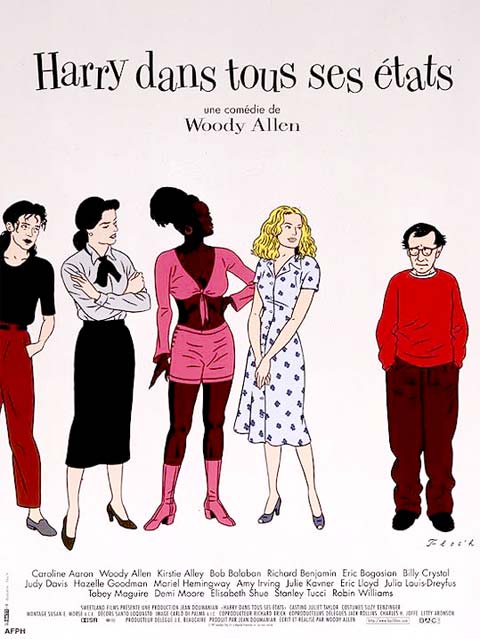

At a point in his career where Hannah and Her Sisters and Radio Days are his “earlier, funny films,” Woody Allen has finally managed to start making Woody Allen movies again.

Maybe they’re essence du Woody, a concentrated dose of his different moods. It was unabashed sentimentality that made Everyone Says I Love You

buoyant, not the familiar gags about Upper East Siders or the

perfunctory presence of Julia Roberts. And it’s shameless narcissism

and navel-gazing that makes Deconstructing Harry, for the most

part, a cynically good time. Only at the very end, when he starts

feeling sorry for himself, does Woody’s most acerbic picture since Stardust Memories lose its way.

The film is constructed, mainly, as a series of short stories,

or jazzy riffs on reality. They’re accompanied by jump cuts that work

in counterpoint to the standards on the soundtrack and further evince

protagonist Harry’s fragmented experiences of life. (Allen’s longtime

film editor Susan E. Morse pulls this off with as much aplomb as

possible.) Allen himself plays Harry, and how could it be any other

way? Foul-mouthed and destructive, this latest version of the neurotic

New Yorker seems to cut closest to Woody’s own bone. Harry Block is a

reputedly brilliant novelist who manages to alienate a steady stream of

friends, (ex-) wives and (former) lovers through relentless pessimism

and self-absorption. Worse, thinly veiled accounts of his private life

with them show up as raw material for his novels. (Only the names are

changed, by a letter or two.) He’s a Jew who has big problems with

Judaism, and he’s a womanizer and three-time divorcee who considers a

happy marriage intolerable.

The storyline, thin as it is, has to do with Woody’s — er, I

mean with Harry’s impending trip to his alma mater (shades of Ingmar

Bergman’s Wild Strawberries), which expelled him all those

years ago but now wants to honor him. The problem is he has nobody to

take along with him. Searching frantically for companionship, he has to

deal with an ex-wife (Kirstie Alley) who won’t let him take his son to

the ceremony, an old friend (Bob Balaban) who’s complaining of chest

pains (the most important words in the English language, Woody muses,

are “It’s benign”), and an earthy black hooker (Hazelle Goodman, who is

terrific in what’s finally a role of some um, substance for an African

American in a Woody Allen movie) with whom he slept the night before.

It’s all strung together in five- or 10-minute episodes, and

the first half of the movie has the easy rhythm of a stand-up routine,

with characteristic zingers and one-liners aplenty. The dialogue is

brazen and profane, resorting to even more fellatio jokes than Boogie Nights.

The basic tone is set in an early scene, when Harry tries to persuade

Judy Davis to put that gun back in her purse by arguing that he’s

fundamentally unhappy anyway: “I’ve squandered everything I have on

lawyers, shrinks, and whores!” When his atheism becomes the subject of

an argument, he shoots back: “We’re alone in the universe — you’re

going to blame me for that, too?” Women are not only troublesome, but

are repeatedly tagged with very vulgar epithets beginning with the

letter C. With one reasonably graphic sex scene at the very beginning

(in one of Harry’s pieces of semifiction), means this may be the first

Woody Allen film to have flirted with an NC-17 rating.

Is it funny? Oh, yes. It’s very funny. Wickedly, bitterly

funny. Allen’s dialogue hasn’t been this sharp in many years. As Mel,

an actor with an unusual problem, Robin Williams has a cameo that

recalls the comic vigor of an Allen screenplay at its most charming.

Billy Crystal plays Larry, a friend who Harry thinks may be the devil

incarnate (a trip to Hell late in the film will sort things out),

particularly when he steals away Harry’s current flame Fay (Elisabeth

Shue). Davis generates some sparks early on, with a brief, fierce (and

witty) performance that testifies to Harry’s apathy and recklessness

where relationships are concerned. By the end of the movie, though,

Harry’s friends are treating him like a lovable old curmudgeon, and

whatever edge his character had is rather deliberately softened.

Of course, there are good reasons to believe that Deconstructing Harry should be read as Deconstructing Woody.

Comedy’s rarely this funny unless it’s genuinely personal. And if this

whole film can actually be interpreted as Woody thumbing his nose at

his detractors from the comfort of the couch in his therapist’s office,

what can we really expect? That at the end of the film he’ll indict

himself as an unlovable bastard? No — even though Woody cuts Harry

enough slack to hang himself with, both the director and his character

remain unapologetic. Finally, the movie lauds Harry’s creative genius,

arguing that even if Harry is a mess as a human being, he redeems

himself through his art.

Well, OK. Woody himself has earned that much, on Harry’s

behalf if not his own — even though the way he sticks the sentiment

into his movie is a little clumsy. And I’ve gotta say that, even if Deconstructing Harry

is a mess as psychology, it’s great comedy. Given its flaws, I may

still rate it too highly — deduct a full letter grade if you’re not a

fan — but how else to convey the good time that I had? The cast is

uniformly grand, and Woody/Harry only embarrasses himself when he makes

his play for sympathy. In the end, like Larry and Fay, I love him in

spite of himself. B+