When I sat down again with Wings of Desire, showing it to a friend who had not yet encountered it, I approached it, as always, from the skeptic's viewpoint. Once again, I was ready to interrogate my own feelings toward this, one of my very favorite movies.

When I sat down again with Wings of Desire, showing it to a friend who had not yet encountered it, I approached it, as always, from the skeptic's viewpoint. Once again, I was ready to interrogate my own feelings toward this, one of my very favorite movies.

I've always considered my own initial feelings on movies a little suspect, particularly if I first saw the film under circumstances that might lead me to make more of the picture than is actually there. I saw Wings of Desire under ideal circumstances. I was a sophomore in college, my arms thrown wide open to embrace anything on campus that resembled a life-changing experience. I saw it in the company of friends and friends-to-be and was taken by the film's unique meditative warmth, its subcurrent of angst and dissatisfaction, and, perhaps most of all, its audacity. I had a passing familiarity, after all, with those giants of the foreign cinema — Bergman, Bunuel, Kurosawa — but none of their films boasted soundtrack music by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, or asked so unassuming an icon as Peter Falk to play himself as a wise old angel.

The story unfolds in monochrome. It's not black and white (although it certainly plays that way on TV). There's a blue tint to all of the scenes, which may be appropriate considering the film's German title: Der Himmel Uber Berlin. In English, that means The Sky or The Heavens Over Berlin, take your pick. Wenders' cinematographer is the grand old Henri Alekan, who many years earlier photographed Cocteau's magical Beauty and the Beast. The circus in Wings of Desire is actually named the "Circus Alekan" — but I'm getting ahead of myself, and I don't want to give too much away.

The film itself is bookended by poetry. The poem in question is written by the director and his co-writer, the German poet Peter Handke, who helps bring this dangerous conceit to convincing fruition. "Als das Kind Kind war," writes angel Damiel (Bruno Ganz). That translates into English as "When the child was still a child" ... it sounds better if you can appreciate the original German. That child, Damiel tells us, was full of impudent, lively questions about the world. (As it turns out, Damiel aspires to be that child.) The journal where he writes his verse may well be the same journal where he takes daily notes on human existence in the divided city of Berlin. Periodically, he takes a seat next to his angel friend, Cassiel (Otto Sander), and the two of them reflect on the day past, cataloging moonrise and moonset and dwelling on the most inexplicable human behaviors. These angels, you see, move unseen among the citizenry of Berlin. They listen in on private thoughts. They are made privy to the rationale of family squabbles and suicides. As they wander, they occasionally take an active role as guardian angels, whispering comforting words in the ear of a dying accident victim, rousing a metro rider from his dark depression, or trying to talk a jumper down from the ledge overlooking city streets. They're sort of like cops on the spiritual beat.

All this human drama fascinates Damiel, whose visit to the circus crystallizes his longstanding angelic melancholy and makes his yearnings flesh. For it's there that Damiel meets his own angel. Her name is Marion (Solveig Dommartin, who will reappear in Wenders films), and she's as lovely as can be imagined. She performs nightly, swinging from a trapeze with a pair of rather tawdry angel wings pinned to her back. Damiel is mesmerized; he sits among the children in the stands and gazes with a child's delight at the modest wonderment of this little misfit circus. Cassiel, meanwhile, stalks around in the shadows, unsmiling. Perhaps he grows perturbed at his friend's wide-eyed fondness for humans.

Like so many matched pairs in Wings of Desire, Damiel and Cassiel are a study in opposites. Damiel is honest, enthusiastic, and yearns to touch, taste and feel. But Cassiel is wary and dry, seemingly long since sapped of all passion. He betrays no such jealousy of the human animal, but in these scenes we can already sense his quiet frustration, buried beneath an angelic shroud of denial. Late in the movie, Cassiel will wander across the stage where Cave and his band are performing a song called "From Her to Eternity." He leans against the wall and closes his eyes, and the stage lights cast three different shadows off his body, alternating and shifting position and color as though we're watching Cassiel's very essence fragmenting before our eyes.

Peter Falk is in Berlin, too — perhaps he's a symbol of Wenders' increasing fascination with America. The essence of America was embodied by Dennis Hopper in Wenders' earlier The American Friend, and by Harry Dean Stanton in Paris, Texas -- if you ask me, a riff on John Wayne's classic archetype in John Ford's The Searchers. By the time Wenders makes the cliche-ridden Until the End of the World, he has seemingly embraced America in its entirety; paradoxically, he has also crafted a sprawling road movie-cum-science fiction epic that veers all the way across the planet and winds up taking root in Australia. But that's another review.

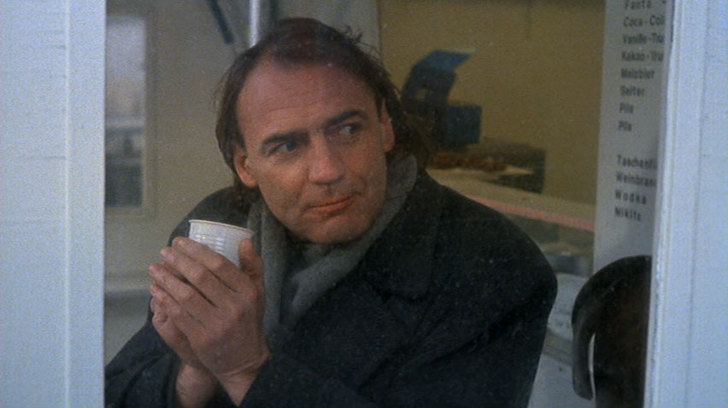

Falk is shooting an unnamed TV movie, and the locals know him as Columbo. He startles Damiel — and us — when he turns to him at a hot dog stand and announces, "I can't see you, but I know you're there." Why in the world is Falk the only man in Berlin who can sense the presence of an angel? And does it have anything to do with the fact that he's an American — a free spirit, of sorts, in this divided city? We'll see.

Wenders' parable swells into one big happy ending, almost deliriously contented. The upbeat resolution is perhaps uncharacteristic of Wenders' films, and it is therefore indicative of his great feelings of optimism where his divided homeland is concerned. To Wenders, the reunification of Berlin is an affirmation that the city has a single history and, perhaps more importantly, a single future. But more than that -- the duality of East and West Berlin is the duality of the human spirit. The Berlin Wall divides the city no more sharply than does the gulf between the physical and the spiritual, between actions and morals, between men and women. One day, Wenders seems to be imploring us, we can find a way to unite all of these things. He does his own work, uniting the mortal and the angelic that his story has created, the woman and the man.

And several years after the movie's release, the world did its part, tearing down the Berlin Wall in an act no less deliberately symbolic than anything that ever flickered across a movie screen. It may have been impossible for a Wenders fan to watch those television reports of the wall being pulled down by firelight, block-by-block, without imagining that flock of invisible angels circling in the sky above Berlin, at long last throwing back their heads and laughing.

And now, with some 10 years of hindsight, how exactly do I look back on one of my most favorite films? With the knowledge that its creators seem to have become friends of mine. Companeros. The universal appeal of Wings of Desire has to do with the way that it addresses not merely angels above a divided city, but all of us struggling with the divided natures of our lives and our souls. Maybe all of us, at some point, are dear Damiel, seeing the world in color for the very first time, looking for a place to trade in the trinkets of our past for the building blocks of our future. And so it is that, for all of us, Wings of Desire posits a happy ending.

12/22/06 update: The current DVD version of Wings of Desire makes it clear that the black-and-white footage is, in fact, meant to be monochrome. Because much of the film is in color, prints needed to be made on color film stock — thus the unintentional bluish tint of theatrical prints, and the older video versions that were made from them. A+

On the threshold of no-man's land, the immortal poet's voice is found..

Now.

(And I'm off to find the written work.) Thank you for sharing.

AM