![[Deep Focus]](../../flicker/logo.gif) |

|

|

THE PILLOW BOOK | |

|

GRADE: B- |

|

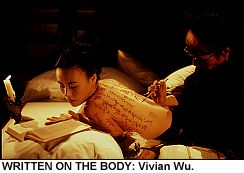

It's a truth long held to be self-evident that sex sells popcorn. Despite all the clumsy American evidence to the contrary -- think of ballyhooed flops like Showgirls and Strip Tease -- shills for foreign film still fall back on the promise of naked flesh to rope customers into the art house. Fortunately for the American art house, British director Peter Greenaway's films have never been lacking in the "acres of naked flesh" department. The conundrum for his distributors has always been how to sell the sex while soft-pedaling the grimly cerebral musings on human nature that skulk around underneath the oh-so-photogenic surface. His greatest triumph to date, at least in the popular mind, is his 1989 critique of the political and social misdeeds of Margaret Thatcher's England, The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover. That tale of a splendid restaurant and one very unsavory customer had a ratings controversy on its side -- the newspaper tag lines, courtesy Miramax, read "X for Exceptional" -- as well as a general outrage against its graphic depictions of coprophagy, meat-truck adultery, and finally cannibalism that could be perceived as stodgy. But maybe that stodginess was a defense mechanism. If Greenaway was criticizing a social order, surely he considered his audience a part of that social order -- and therefore as ripe a target as any for his intellectual savagery. His visual collaborator on The Cook, The Thief was Sacha Vierny, surely as magnificent a cinematographer as any. Vierny made his reputation shooting the hypnotic Last Year at Marienbad and Muriel for Alain Resnais, that standard-bearer of the most experimental movement of the French New Wave. Vierny continued to work with Greenaway on Prospero's Books, a phantasmal interpretation of The Tempest that surely features more naked bodies -- dozens, maybe hundreds of them -- than any other film in history. Greenaway has been accused of harboring a distaste for the naked human form, but I don't think he fills his pictures with nude bodies out of spitefulness. Rather, he's absolutely unsentimental about the carnal possibilities represented by an unclothed body. (As far as I can tell, the notion of cinema as voyeurism has almost no meaning or resonance at all in the context of Greenaway's very controlled work.) By refusing to arouse his audience, or to allow his own films to be made tumescent by their strangely anerotic imagery, Greenaway exudes a detachment -- and an unsmiling fascination with the vulgar -- that can be intepreted as misanthropy. Certainly it takes some doing to strip such world class beauties as Julia Ormond and Ralph Fiennes absolutely naked on a movie screen without so much as a tip of the hat to prurience. But by the end of a centerpiece lovemaking sequence in the middle of The Baby of Macon, those two international superstars have prostrated themselves nude at the altar of Greenaway. Covered in blood, Ormond will be dragged away only to be raped by hundreds of men in a Greenaway set piece so notorious that it basically guaranteed The Baby of Macon would never see the light of day in the United States. Miramax, Greenaway's ever-resourceful U.S. distributor for four films running, took a pass. As of this writing, The Baby of Macon has been seen only at scattered screenings in the U.S. I only hold forth on all this because I think it may have some bearing on the way The Pillow Book came out. Greenaway has described his own tendency to veer back and forth between commercial projects and less palatable concepts -- sort of the way Woody Allen used to mollify his studio benefactors by making sure that every second or third feature was a comedy starring Woody Allen. If Prospero's Books represented a comedown from The Cook, The Thief in terms of commercial potential, The Baby of Macon was surely a bottoming out. Considering his next move, it's no wonder he decided to dip back into Prospero's bag of electronic tricks in the service of what could be conveniently described in ad slicks as a "richly sensuous" tale. It is a lush concept, after all. The Pillow Book is the story of Nagiko, a Japanese woman who develops a profound appreciation for the sensual pleasure of having calligraphy written on her body. Growing up, her mother reads to her from the 1,000-year-old Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon, and her father paints her face every year with a birthday greeting telling a creation story. Nagiko is scarred (or at least puzzled) at the age of 5, when she spies on her father having sex with his homosexual publisher in return for money and publication, and again at the age of 18, when her marriage is arranged to a man who cares little about Nagiko's sensual pleasure. When her husband jealously sets fire to Nagiko's diaries -- her own pillow books -- Nagiko flees Kyoto for Hong Kong. Perhaps implementing a lesson learned from her father's affairs, the adult Nagiko (Vivian Wu) searches for lovers who are great calligraphers by offering them sex in exchange for their writing on her body. Eventually, she winds up in bed with Jerome (Ewan McGregor), a charming Westerner whose penmanship leaves something to be desired. It's Jerome who encourages her to write on the bodies of others -- perhaps allowing her to take control of her own destiny. Along the way, Nagiko learns that Jerome is also having an affair with her father's former publisher. When the publisher rejects her own attempt at a manuscript, Jerome gives her the idea of composing the text on his own body, so that he can present it to the publisher. The Pillow Book seems occasionally frivolous in its plot contrivances, but the imagery is tremendous. Wu may be limited as a performer, but she has a marvelous look about her, and Vierny's camera investigates every contour of her body, her breasts ringed with prose and her nipples the color of gold. And when the ever-charming MacGregor appears, the audience perks right up. His body is subject to even more intense scrutiny than Wu's, which is a novelty in itself. (The movie bears a 1995 copyright date, suggesting that MacGregor may have completed shooting just before going to work on Trainspotting, which made him a star.) A dozen more male performers function as nude walk-ons, their bodies covered in magnificent script. Greenaway didn't bother taking this to the MPAA for a rating, and it's just as well. I can't remember a nonpornographic movie ever taking such a long look between a man's legs, and I can't imagine that such scenery would ever pass R-rated muster. If The Pillow Book demands that we feast our eyes on a literal "body" of written work, the technological aspirations on display are even more fascinating than the reams of human flesh. Like Prospero's Books, The Pillow Book is a film made in layers, opening windows on top of windows and placing frames within frames. (Don't wait for the video.) Subtitles appear and disappear on the screen, rendered in fancy script that translates the original Japanese. The backdrop for the opening scenes is page after creamy page of Japanese writings, presumably taken from the titular volume, and sex between Jerome and Nagiko is quite nicely played out behind a smaller cinematic window featuring erotic Japanese artwork that underscores the literary appeal of sex. When the disparate layers of sight and sound actually coalesce to creating something fresh and overwhelming, it's enough to take your breath away. Elsewhere, The Pillow Book is simply ponderous -- as smugly indulgent an exercise in style as you're likely to see in a movie house this year. Most tellingly, the film is stimulating but never seductive. The audience is kept at a remove from the action, never allowed to feel intimacy with the characters or even with the subject matter. Arguing that cinema is a 100-year-old technology nearing the end of its natural life span, Greenaway claims in interviews that he's striving toward a new way of telling cinematic stories. But in that, his hubris is nearly as annoying as his audacity is gratifying. The presence of Vierny makes for an unflattering comparison -- working with Resnais and the writer Alain Robbe-Grillet, Vierny was a party to a theoretical deconstruction and interrogation of cinematic narrative itself that Greenaway is no doubt aware of. Regardless, The Pillow Book's pretty stylistic tropes seem to exist only for their own sake. Interestingly, I found myself missing the stately elegance of Michael Nyman's scores for The Cook, The Thief and Prospero's Books. (After all, with such a lovely score, Greenaway might even have gotten away with the wantonness of The Baby of Macon.) Instead, the selection of music for The Pillow Book is both portentous and jarring -- who would have thought that U2 would ever show up on the soundtrack of a Greenaway film? Finally, I sense a feeling of duty that belies The Pillow Book's moments of quiet beauty and tragedy. After dishing out visual poetry, an uncharacteristically traditional narrative, and dazzling but icy visual stylings for about half the film's length, Greenaway once again turns on his audience with a spiritedly grotesque sequence involving a suicide and the exhumation of a spurned lover's grave. But after the ensuing virtuosic presentation of 13 different bodies painted with 13 different "books," this bizarre tale reaches a rote, unconvincingly optimistic conclusion -- you get the sense that, for the first time, this most contrary of directors may give a damn whether the general audience cares for his film. Worse, the effort may be in vain -- for a film that takes such a painterly approach to the canvas of a nude body, The Pillow Book itself is cloaked in too many stiff layers of ostentatious experimentalism.

| |

|

Written and Directed by Peter Greenaway Cinematography by Sacha Vierny Edited by Greenaway and Chris Wyatt Starring Vivian Wu, Ewan MacGregor, and Yoshi Oida USA, 1997 The best Greenaway resource on the Internet remains Bruno Bollaert's Peter Greenaway: the internet version. Another site is devoted entirely to Prospero's Books. | |

| |

http://www.deep-focus.com/index.html

bryant@deep-focus.com

http://www.deep-focus.com/index.html

bryant@deep-focus.com