![[Deep Focus]](../../flicker/longo.gif)

Dance, babies.

![[Deep Focus]](../../flicker/longo.gif)

|

|

| The Company |

|

|

A- |

|

Dance, babies. |

|

|

Movie Credits: Directed by Robert Altman Written by Barbara Turner from a story by Turner and Neve Campbell Cinematography by Andrew Dunn Edited by Geraldine Peroni Starring Neve Campbell, Malcolm McDowell and The Joffrey Ballet of Chicago USA, 2003 Aspect ratio: 2.35:1 (HD) Screened 12/03/03 at Sony Screening Room, New York, NY Reviewed 12/07/03 Off-site Links: There's already one movie about "Blue Snake." |

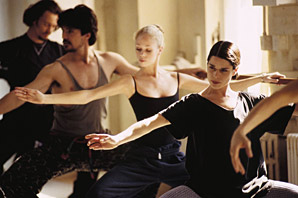

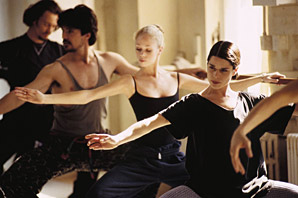

Because Robert Altman's known for fairly dense, multi-layered storytelling, The Company comes as a surprise. It's clearly an Altman film through and through, with multiple narrative threads following an array of protagonists through their daily paces and that sinuous, probing camera, moving slowly forward into the action from cut to cut. But those threads are unusually slender, with characters defined through observation. Because The Company is about the Joffrey Ballet of Chicago, one of Altman's subjects here is the way talented young people make their way in the real world. When we learn that Neve Campbell's character makes a living by pulling on a Louise Brooks wig, and waitressing at a club, Altman's commentary on that situation is clear but decidedly subdued. Isn't that something, that the girl bringing you mojitos at two o'clock in the morning is a world-class ballerina with blisters on her feet and an a.m. rehearsal to make? OK, Neve Campbell's not a world-class ballerina. She is, in fact, the only actor portraying a Joffrey dancer in the film — everyone else is the real deal. But Campbell trained as a dancer when she was a girl, and she doesn't stick out as badly as you might expect. The camera is very kind to her. Campbell shares a story credit on the film — the screenplay by Barbara Turner was written specifically for Altman, once he came on board the project — which apparently speaks to her own fascination with the everyday life of the professional dancer. The Company does romanticizes the ballet, and draws on clichés about the dancing life. There's the brilliant but arrogant taskmaster, here played with flamboyant brio by Malcolm McDowell, full of complaints, compliments, and sage advice. (“It's not the steps, babies,” he says. “It's what's inside that really counts.”) There's the aging diva, as well as the younger dancer who's cut from the program at the last moment. There's the — crunch! — crippling injury. Altman seems genuinely entranced by all of these elements. The Company doesn't aspire to be an insider's look at the world of dance, nor does it have the presumptiveness that such an endeavor would entail. The audience has a privileged perspective, but it's clearly that of omniscient spectator, not participant. That position is evident nowhere as clearly as it is in the film's lengthy performance sequences, which function almost as high-end documentary, with a God's-eye view of the completed dance on stage. Cinematographer Andrew Dunn shot the film in HD, which allowed complete Joffrey performances to be photographed using multiple cameras; the widescreen assemblages, by editor Geraldine Peroni, are breathtaking. In fact, this is the first motion picture I've seen with an aesthetic that could be said to have been enhanced, rather than limited, by its digital cinematography. The film opens with a breathtaking performance of “Tensile Involvement,” which involves eight dancers and a web of elastic ribbon, that's all electric motion, Dunn's camera making smooth lateral moves as the stagelights bloom behind the dancers in startling primary colors. When the ribbons snap taut, it's like a spark crackling across the screen. Elsewhere, the HD medium is limiting — the white backgrounds of exterior scenes are blasted out, and the edges of objects on screen can take on artifically severe edges, but those limitations themselves can be beautiful, as in a sequence where a single dancer on wires touches lightly against the stage floor, the flat background behind her alive with bluish video grain. If the picture in general looks a little soft, Dunn has managed to give it a delicate, almost classical haze that suits the material. The narrative stops dead at regular intervals to showcase performances, including the show-stopper that takes place on an outdoor stage in Grant Park during a rainstorm. For a dancer, this stuff is high melodrama, and Altman knows it, so he milks it for all it's worth, with thunder rumbling ominously through the skies in the minutes before Campbell and dance partner Domingo Rubio are set to take the stage for a delicate pas de deux. Once the skies open up and the wind sweeps across the stage, the dancers are committed — the crucial question becomes whether there's standing water up there. Altman shoots the sequence to depict the quiet, committed intensity of everyone involved, from the performers and umbrella-toting spectators to the trainers watching from folding chairs and even the technicians controlling the show from the wings. If you pay close attention to the overheads of the Grant Park scene, you'll note that plenty of empty seats can be seen, which may be an acknowledgment of the less-than-overwhelming level of public support for ballet. And as wunderkind choreographer Robert Desrosiers concocts a whacked-out magnum opus to be consummated by the Joffrey troupe (actually “Blue Snake,” first performed by the National Ballet of Canada with an impressionable 9-year-old Campbell in the audience), he's continually admonished to keep in mind the Joffrey's decided lack of budgetary largesse. That doesn't keep the Joffrey from mounting a full-on production of “Blue Snake” with crazy, stylized costumes — it reminded me of a Very-era Pet Shop Boys video — and a dancer-chewing Olmec head, with flailing stone fists, at the back of the stage. What's Altman's take on it? Hard to tell. Presumably he approves of the risk-taking, and, although Desrosiers comes across as a bit of a crackpot in the few scenes showing him explaining his vision to the dancers, Altman mostly resists obvious opportunities to underscore the piece's Spinal Tap-style pretensions. (I can easily imagine McDowell, at the end of his rope, spitting “No, we're not going to fucking do 'Blue Snake!'”) Instead, he just captures the performance with a grace and attentiveness that makes a virtue of the outré staging, special effects and costumes. Once that performance was underway, I was just a little surprised to realize that the film had obviously reached its climax. That's interesting because, honestly, there's no story to speak of. There's an understated romantic courtship between Campbell and James Franco, playing a sous chef, and a number of dangling threads that involve a flophouse apartment for struggling dancers and some minor tension among the dancers themselves, but Altman has little interest in resolving them or drawing conclusions. There are no pitched rivalries between dancers, romantic or otherwise, no bids to jerk tears and no ham-fisted “inspirational” moments. Instead of culminating in any narrative denouement, the film gives us a dance-your-hearts-out performance piece and then just stops, our window on the world of the Joffrey closed. In retrospect, The Company's stripped-down narrative style reveals a lot about what makes the best films in Altman's ouevre so indispensable — it's their clarity of vision, and their belief that stories can always be found if you're committed to watching people carefully enough. And if The Company is destined to be dismissed in some quarters as “minor Altman,” I'd argue instead that it's the director's unassuming approach that makes the film an unpretentious joy and a major achievement. It's like a little poem — breathtaking in its simplicity and commanding in its control of the medium. |

http://www.deep-focus.com/index.html

bryant@deep-focus.com

http://www.deep-focus.com/index.html

bryant@deep-focus.com