![[Deep Focus]](../../flicker/logo.gif) |

|

|

THE CELL | |

|

GRADE: C+ | The playground of my mind. |

|

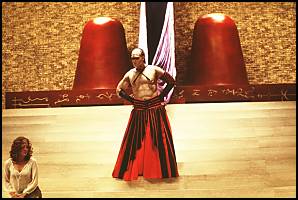

Mediocre detective story meets shallow psychodrama in a fanciful serial killer yarn with jaw-dropping visuals (and an excellent score by Howard Shore). Director Tarsem Singh should probably direct a widescreen movie musical next — it’s clear that surreal imagery is more important to him than narrative, and even The Cell’s more astounding moments don’t approach the lofty heights scaled by his earlier masterpiece, the music video for R.E.M.’s “Losing My Religion.” Apparently unable to get Madonna, Tarsem cast Jennifer Lopez as Catherine Deane, the empathetic psychologist who has a knack for getting inside people’s heads. Specifically, she uses a science-fiction technique that involves placing two people in red rubber suits, suspending them from the ceiling, and allowing one of them to enter the psyche of the other. As the movie begins, she’s making progress communicating with a comatose little boy. But her job description changes when the body of captured serial killer Carl Stargher (an appropriately manic Vincent D’Onofrio) shuts down before anyone can ask where his next victim is locked up. At the behest of bland FBI agent Peter Novak (Vince Vaughn), Catherine ventures inside Stargher’s head to try to convince his subconscious self to give up the information. Trouble is, if Catherine loses her bearings and forgets that the phantasmal realm within the killer’s head is imaginary, then any harm that befalls her in that psychic realm could be deadly. The obvious antecedents for this stuff are science fiction movies along the lines of Brainstorm and Strange Days and horror movies like A Nightmare on Elm Street. Most specifically, it draws from Manhunter and The Silence of the Lambs, both of them based on novels by Thomas Harris, the most wildly successful chronicler of cop-killer relationships. The Cell tops them all in terms of sheer visual imagination, but comes up slack in the realm of story and character. Specifically, the scenes that take place inside the psychological realm are stunning, combining the lavish, story-be-damned sensibility of an MGM musical with the audacious sensibilities of a LaChapelle photograph. An S&M; king who recalls Tim Curry’s devil from Legend rules a kingdom of big-breasted bodybuilders, human-sized Barbie dolls, and boyhood traumas. Trouble is, nothing is really at stake inside that realm — The Cell is like two unrelated movies bumping heads, one of them a surreal psychological thriller and the other a straightahead save-the-victim mystery along the lines of Kiss the Girls or The Bone Collector. Novak tries to save the killer’s next victim while Catherine (eventually appearing in full virginal splendor) tries to save his soul, but, bafflingly, the two quests are unrelated in any practical sense, despite some deft cross-cutting. Let me tell you this -- if the cops and detectives from your typical paperback mystery novel were put on this case, they’d solve it inside two hours with a few phone calls and no resort to quasi-psychological hocus-pocus. This may be an increasingly rare example of a Hollywood thriller with too few plot twists for its own good. Also problematic is the casual repugnance of the story. The serial killer in question is a mess of a human being — heavy into torture, body modification, and masturbation, he’s the type of specimen that might rampage through the world of Todd Solondz’s Happiness. But he never feels real, and he’s certainly not scary. He’s a constructed boogeyman. A childhood-abuse subplot is trotted out in order to — well, in order to what? To help explain (and thus excuse?) his behavior? To win our sympathy? It doesn’t work. As superior examples of the genre have shown, it’s the most unrepentant of evil men, the ones who know what they are and enjoy being that way, that capture our imaginations and make us shiver in the dark. His victims aren’t any more fully fleshed out. As one woman tries in vain to escape her own cell, the film taps not into her panic, but into Stargher’s sadism. He has four video cameras set up to record her eventual death, and we generally see the situation from his point of view, rather than hers. And because her fate has been spelled out for us in advance, there’s little suspense in wondering exactly what could happen next. The film has some unusually grisly ideas, such as a quasi-erotic fixation on nude, wide-eyed corpses (seen on a morgue table and in evidence photos) that is somewhat daring for Hollywood, but I think it’s too cavalier and self-consciously arty to work as horror. Tarsem is clearly the sort of original, provocative visual stylist that good cinema demands, but only time will tell whether he can really make his ideas cohere and communicate in the context of a feature film.

| |

|

Directed by Tarsem Singh Written by Mark Protosevich Cinematography by Paul Laufer Music by Howard Shore Edited by Robert Duffy and Paul Rubell Starring Jennifer Lopez, Vince Vaughn, and Vincent D'Onofrio USA, 2000

Theatrical aspect ratio: 2.35:1

| |

| |

http://www.deep-focus.com/flicker/

bryant@deep-focus.com

http://www.deep-focus.com/flicker/

bryant@deep-focus.com