|

[ . . . of 1999 | . . . of 1998 | . . . of 1997 | . . . of 1996 ]

Enduring favorites and fetishes |

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (Sony Pictures Classics)

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (Sony Pictures Classics)The best film of the year was, in some ways, the most old-fashioned. Formulaic, cgi-heavy dreck like Vertical Limit showed how crass and artless the Hollywood magic machine has become, but Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon rekindled the world-beating combination of excitement, violence, romance and intelligence that used to distinguish the studio system. It didn't hurt that the all-star lineup, comprising two quintessential Hong Kong bad-asses (one female) plus a gorgeous newcomer, made America's favored action heros look old and tired. Devotees of Hong Kong cinema may still prefer the real thing -- Swordsman II is widely thought to be the pinnacle of the wuxia genre -- but the combination of artistry and craftsmanship on display here is singular and thrilling. |

O Brother, Where Art Thou? (Touchstone)

O Brother, Where Art Thou? (Touchstone)Funny how the Coen Brothers followed up Fargo, which common wisdom considers their masterpiece to date, with the unhinged flight of fancy that was The Big Lebowski and now the completely notional O Brother, Where Art Thou?. O Brother in particular is such a hoot, a shaggy yarn about three escaped convicts who journey through the memory of America with folk songs offering spiritual guidance, that I consider rational criticism moot. Consider it the humane counterpart of Dancer in the Dark, with an equally stirring soundtrack. Anyone who can resist the versions of "Man of Constant Sorrow" on offer here is someone I don't want to go to the movies with. |

Dancer in the Dark (Fine Line Features)

Dancer in the Dark (Fine Line Features)The year's most haunting film was the one that had no business being a success at all. Shooting a musical in a style descended from Dogme 95, casting Iceland's abrasive chanteuse Björk in a lead role and pretending that the landscape of Northern Europe is really the Pacific Northwest, Lars von Trier laughs in the face of disaster and ends up looking like the world-class showman he always suspected he was. By any objective standards, this is silly, manipulative stuff, with von Trier's protagonist once again subject to the sort of misfortune that shouldn't befall a Griffith heroine. But there's a level on which Dancer in the Dark is both precious and consuming, where Björk's trial stirs little whirlwinds of terror and empathy within us. Some viewers will respond and some won't, though I'd think Björk's raw emoting and breathtaking song score would draw at least grudging respect. Von Trier's detractors may argue whether the intensity of conviction he brings to even his best films rivals, say, Dreyer's, but those willing to follow him into the abyss will return feeling stronger for the journey. |

Coming on like he had something to prove, Steven Soderbergh managed to release not one but two world-beating films this year. Erin Brockovich was pretty good, an extremely well-directed movie of the week with a delightful-for-a-change Julia Roberts in the title role. But Traffic is a relatively deep and highly entertaining epic about the hypocrisies and futilities inherent in the American war on drugs. Transplanted to the U.S. and Mexico from a British TV miniseries set in the U.K. and Pakistan, Traffic dismantles U.S. drug policy with an acumen rarely seen in recent mainstream film. Distinguished by outstanding performances (particularly from Benicio del Toro and the great Don Cheadle) and superior storytelling strategy, the whole project is dragged down somewhat by contriving to make Drug Czar Michael Douglas's daughter a goggle-eyed dope fiend and by Soderbergh's overly stylized cinematographic strategy. Quibbles aside, the rest of the picture is an exciting message movie that proves Hollywood can still make exciting message movies. So bring 'em on, folks.

|

Requiem for a Dream (Artisan)

Requiem for a Dream (Artisan)So accomplished it's scary, Darren Aronofsky's sophomore feature saw him make the transition from no-budget to low-budget, easily deploying the sort of trick editing and aural slickness that would have been unthinkable in his previous Pi. Every element is just perfect, from the Clint Mansell score and Jay Rabinowitz's film editing to the by-turns-touching-and-horrifying performance of Ellen Burstyn (don't call it a comeback; she's been here for years). The awesome display of technique, unfortunately, doesn't quite give flight to the accompanying Hubert Selby yarn about addiction and the havoc it wreaks on ordinary lives. Still, this fella's ridiculously talented. Warner Bros. has him in mind for the next Batman movie, and I say good for them -- here's hoping they let him direct in the manner to which he has grown accustomed.

|

Yi Yi: A One and a Two ...

Yi Yi: A One and a Two ... (Winstar) Edward Yang's sprawling family drama evokes a sort of globalized intimacy, stirring a laconic storm of emotion and ambivalence with a restraint that borders on the mystical. In its three-hour duration, Yi Yi touches on the ethics of businessmen, the melancholia of lost love, the stasis endengered by a loved one's illness, and the childhood discovery of the opposite sex. At the center of the story is a middle-aged software engineer who's visited by more or less every disillusionment that adult life can offer. In the tradition of Ozu, I guess, but absolutely contemporary in its concerns. |

The Wind Will Carry Us (New Yorker Films)

The Wind Will Carry Us (New Yorker Films)I'll be damned if I can adequately express what it's really about, but I never really shook the insinuated poetry of Abbas Kiarostami's most recent feature. Casting Behzad Dourani as a filmmaker -- and thus Kiarostami surrogate -- bound and determined to violate the sanctity of a tiny village's death ritual, the director examines his own relationship with the non-professionals whom he photographs. The film derives its title from a softly erotic poem by Foroogh Farrokhzaad, which is recited by Dourani in a darkened cellar to a young woman who is milking a cow for him. (You can imagine the symbolism.) Kiarostami's greatest achievement here may be the documentary-style recreation of the village (and the nearby hillside to which he must hurry in order to take cell phone calls) in such geographic detail that, walking out of the theater, you feel you've actually spent some time there. Otherwise, the film is merely gorgeous, strikingly observed, and, against the odds, really quite funny. |

Almost Famous

Almost Famous (DreamWorks) The seeming effortlessness with which Cameron Crowe makes movies is illusory, no doubt. Whether your star is Patrick Fugit or Tom Cruise, it's clear that making a $70 million studio flick is no spurious undertaking, and it's obvious that the mostly seamless storytelling and utterly charming performances of Jerry Maguire and Almost Famous are the reward of a director who throws his whole heart into his movies. What really works like a charm is the dialogue, which speaks volumes but, when it's working, feels neither labored over nor overly stylized. It's true that this movie makes some gross miscalculations, never really recovering its credibility from the truly lame airplane confessional centerpiece. But of the films I saw this year, only Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon induced the same feelings of euphoria that Almost Famous intermittently offers. |

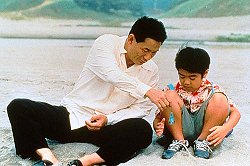

Kikujiro (Sony Pictures Classics)

Kikujiro (Sony Pictures Classics)Maligned by some as mawkish, Takeshi Kitano's sweet-and-sour fable of a boy journeying across the Japanese countryside with a curmudgeonly quasi-thug to meet a mother he never knew is certainly sentimental. But it has a fairy-tale quality that simultaneously welcomes sentiment and keeps it at bay. I'm a sucker for the fantastic dream sequences that visualize trauma and childlike trepidation at the sheer vastness of new experience, and I find Kitano himself to be a fascinating personage. Critic Tom Block, writing for Culturevulture.net, described him here as "a griffin-like fusion of Eastwood and Chaplin," and I can't really improve on that. (Maybe more Keaton than Chaplin, but still.) With a less impassive and dryly comic figure in the title role, I'm not sure how this film could have been a success. But Takeshi brings it off and even makes it affecting. Maybe not one for the ages, but certainly worthy of more generous notices than it received. |

Cast Away (20th Century Fox)

Cast Away (20th Century Fox)This is the closest Hollywood got all year to making the kind of expansive, star-driven entertainment for which it used to be famous. Cavils about the final couple of reels only hold water because director Robert Zemeckis won't stop manipulating the audience, which is actually a hallmark of his films. Despite juicing it up a little too far in the post-island sequence, he is otherwise right on the mark, moving the expository portion of the story as expeditiously as possible toward getting Tom Hanks marooned on that damn island, where he'll be stuck for the bulk of the film. With only an anthropomorphized soccer ball and pictures of his honey for company, Hanks is a one-man Survivor, his plight absurdly made more affecting by the runaway success of that damn TV show last summer. Terrific cinematography, fine storytelling, and courage to spare -- it could only be an actor's hubris that leads Hanks to accept his solitary assignment, and crazy confidence that makes Zemeckis imagine he can make it fly. In short? Good flick. Confidence validated, hubris earned. |

|

Guiltless Pleasures: |