Tabloid

First-tier documentarian Errol Morris finds himself slumming a bit with Tabloid, a clear departure from his recent tendency toward rigorous, serious-as-a-tumor inquiry. He describes it as “sick, sad and funny.” His attention has somehow been drawn to Joyce McKinney, a former Wyoming beauty queen who fell in love with Kirk Anderson, a young Mormon from Utah. Anderson’s family (and the church) disapproved of the relationship. Anderson left the states to work as a missionary in Britain, and McKinney eventually followed him there. That much, at least, is not in doubt. What happened next is open to some question.

Either McKinney (working with an accomplice) kidnapped him, tied him to a bed, and essentially raped him repeatedly over the course of several days, or she rescued him from the thrall of religious zealots who had brainwashed him and treated him to a long weekend of glorious lovemaking that left him racked with Mormon guilt. McKinney denied the assault charges from the start, claiming Anderson was a willing partner. (It seems true that, as a large man, he would have been a handful to contain.) Wikipedia indexes this story, charmingly, as the “Mormon sex in chains case.”

Because Anderson refused to be interviewed for the film and McKinney’s alleged co-conspirator is dead, Morris can’t do much to resolve the tension between those two stories. Instead, he revels in it. (Probably he breathed a sigh of relief when Anderson declined comment.) McKinney’s extended discursions may reveal a worldly sensualist caught in the tug of war between carnal urges and religious propriety, a calculating opportunist with a talent for manipulating men, or simply an aging sex kitten with a propensity for romantic self-delusion. Morris talks to newspapermen — a reporter from the Daily Express and a photographer for the Daily Mirror — who shed some light on how all this was treated in the British media, which feasted on the story. The Express was in bed with McKinney (ahem) and published information she was feeding it, while the Mirror was raking up muck from her past.

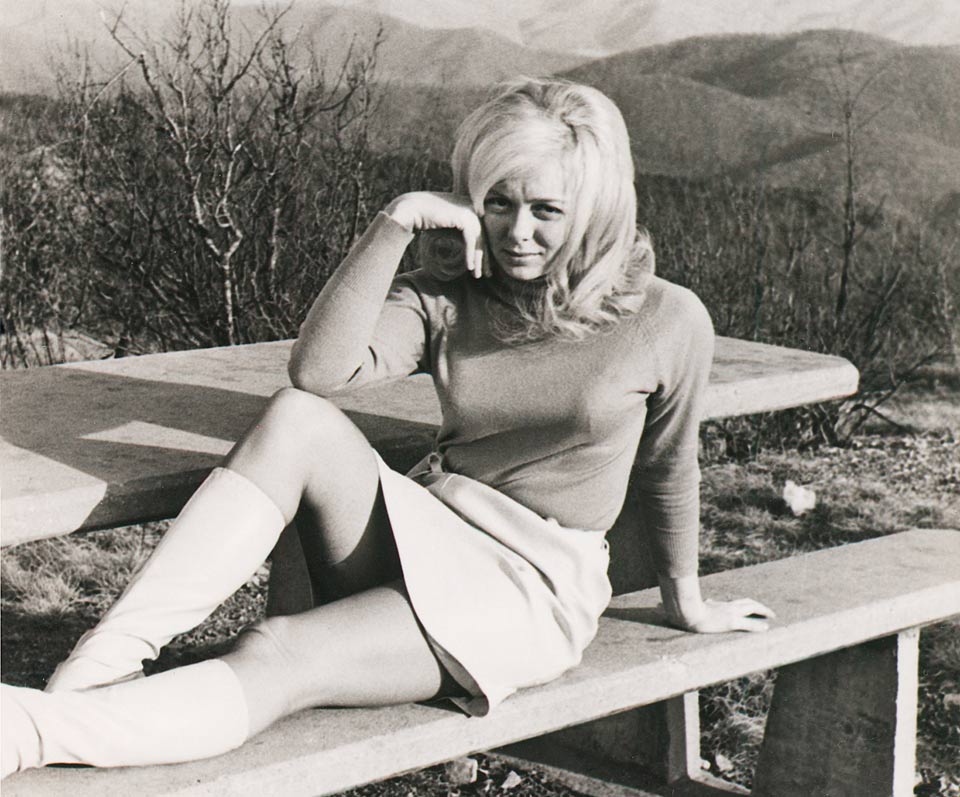

Amazingly, the story is anchored by some lovely 16mm footage from the mid-1980s that shows McKinney reading from a memoir in a fairy-tale setting, which Morris threads throughout the film. (I assumed it was found footage or a clever re-enactment, but the press notes say it’s the real deal.) The interviews are plain vanilla talking-head affairs, but they’re afloat in a sea of elaborate graphic design, allowing Morris to share McKinney’s early beauty-queen portraits, then have them torpedoed by the multiplicity of tabloid headlines that reveled in the whole sordid affair, portraying it in more or less the same reductive, exploitative manner that would grab eyeballs and shift papers. Later, that visual approach well documents the explosion of prurience that occurred when salacious and nude photos of McKinney were discovered.

It’s reasonable to complain that a documentarian’s use of all these materials is plenty exploitative in its own right, which is probably true, but in Morris’s hands it all becomes a big, self-reflexive joke — he’s made a film that’s not only descriptive of tabloid journalism but exemplary of the form. Was McKinney guilty of sexual assault? By the time Tabloid is over, you might wonder, “Who cares?” Pass the popcorn.

Posted by on July 15, 2024 7:59 AM