The Brown Bunny

“If people are sitting there watching The Brown Bunny and waiting for the motel scene, then I just can’t relate to them,” says Vincent Gallo, who directed himself in a “motel scene” where he receives head from Chloë Sevigny. “Maybe I was being idealistic or possibly insane, but I didn’t think people would concentrate so much on the sex scene,” says Sevigny of her own performance. Those quotes are from the press kit, in which both Gallo and Sevigny profess surprise that the inclusion of a hardcore sex scene in an otherwise understated indie film would draw a certain prurient interest from the press corps. It would be impossible to credit these two pros with this level of naivete — if you don’t want to draw attention to a scene, it’s probably a good idea not to have your lead actress fellating you in close-up in that scene — if the film itself weren’t such a heartbreaker. The Brown Bunny is intimate enough, and Gallo’s own performance is so naked and fearless, that it’s just barely possible to believe that he’s nutty enough to have expected viewers to engage with it fully and react to it with measured thoughtfulness.

Get The Brown Bunny on Blu-ray from Amazon.comTo make The Brown Bunny, Gallo loaded his vintage production package into a black van and started driving cross-country from New Hampshire to Los Angeles, picking up scripted scenes along the way with a couple of 16mm cameras. He claims never to have had more than three people traveling with him, presumably including the two camera operators and gaffer cited in the credits, and shot some scenes (including the notorious motel-room tete a tete) with no crew at all. This is notable because the DIY aesthetic lands the film squarely in the tradition of personal cinema and lends it an evocative, moments-out-of-time feeling. Seemingly endless scenes are shot through a stained windshield as the American continent passes by outside, Gallo’s scruffy mug is consistently framed off-center, and the performances and dialogue have an immediacy born from looseness and simplicity. It’s a sadly beautiful home movie.

Even before Cheryl Tiegs shows up in a rest-stop cameo, the apparent points of reference are America in the 1970s. A strong early scene has motorcycle racer Bud Clay (Gallo) visiting the parents of Daisy (Sevigny), his girlfriend back home in Los Angeles, who don’t remember him. (Also, they’re keeping a small pet bunny that they claim belonged to her; Bud is skeptical, bunny lifespans being what they are.) The sequence is awkward and, in a way — her apparently age-addled father occupies a corner of the frame like a home furnishing — almost funny. But what hits spot on are the details in the background, like the stainless-steel coffee pot tucked among the other elements of a kitchen that time forgot. Here and in Buffalo ’66, Gallo plumbs a style of Americana that’s less often represented on film these days — the ordinary landscapes of ordinary cities, the banal ribbons of highway that connect one American town to the next and one coast to the other, the wide-open white spaces of Utah’s salt flats. Because Gallo’s approach is unhurried — even cut to 92 minutes from the two-hour workprint that was shown at Cannes last year, the film feels languid in its pacing — these images come at a gentle, patient cadence that encourages contemplation, and despite being digitally blown up from 16 to 35mm prints, the celluloid has retained a beautiful old-school grain.

The narrative eventually suggests the open road as a metaphor for the highways of Bud Clay’s mind. There’s a reason why Bud is drawn, repeatedly, to vulnerable women, each named after a flower, with the urge not to fuck them so much as to protect them, and it has to do with the spectre of his relationship with Daisy. When Daisy actually arrives on the scene, she’s not a girlfriend but an idealized creature, a phantasm projected into a tawdry L.A. space by a tormented mind.

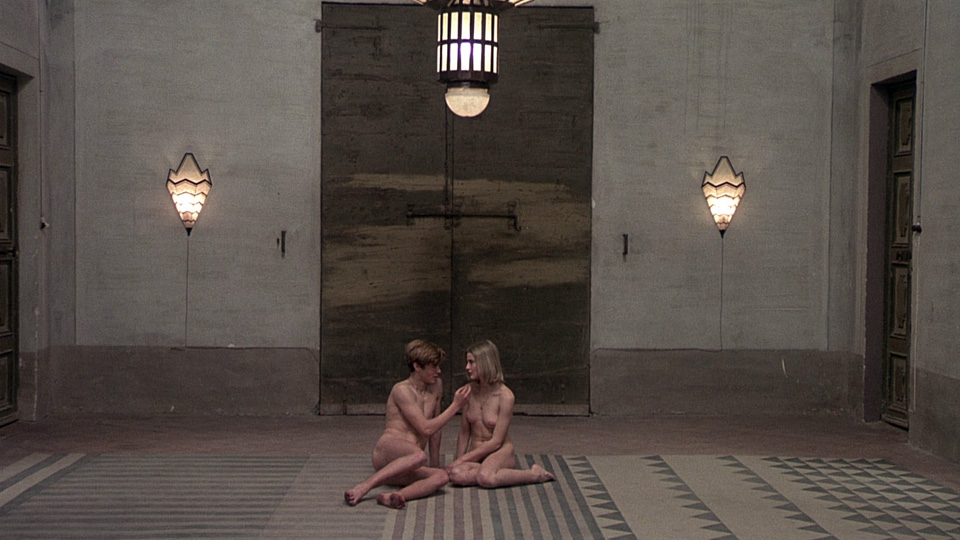

It’s here that Gallo is most open to charges of narcissism — after watching something like 75 minutes of close-ups of his own face, how else are you supposed to take it when you notice that the director is quite literally having his actress suck his cock? — but then the bottom falls out, and The Brown Bunny is suddenly dealing not just with the loneliness of the road but also deep and painful pangs of loss, regret, mourning, self-loathing. The Brown Bunny is testimony to the ways in which explicit sex can be used to illuminate real questions of character and motivation. What’s most interesting about the sex scene is, in fact, that Gallo takes it so far over the top — not only does Sevigny blow him, but she also tries to answer his questions while she’s doing it, resulting in a series of muffled vocalizations that suggest her status as a passive, unempowered receptacle that Bud’s plugged himself into. If it’s an act of exhibitionism by the director, it’s also clearly an assertion of unearned sexual authority by the character he’s playing, and thus entirely germane to the point of the film. Only afterward, as Gallo curls up on the bed and sobs, does it become apparent that the scene expresses something about mental representations of people — the passivity that we sometimes expect them to assume, and the halo of perfection that we sometimes wish upon them — and Bud’s own emptiness.

If The Brown Bunny feels weirdly indulgent, it’s nothing if not a fiercely personal film — a work of art conjured in the spirit of poetry — and it’s impossible to dismiss as an ego trip any undertaking that runs such a risk of making its auteur look foolish. I have to admire the gumption exhibited by anyone who would make a film in this way — hitting the road with a couple of cameras and a weird idea, clearing oddball songs by artists like Gordon Lightfoot and Jackson Frank, calling up an old girlfriend and asking for a big favor. And when deciphering the films made by a public personality like Gallo, the lines between character and filmmaker start to dissolve. (Gallo himself has repeatedly expressed irritation at this tendency by reviewers to equate filmmaker with character, and while I understand his frustration I think the equation is inevitable — it’s like trying to separate the icon that was Katharine Hepburn from the ways that her essential Hepburn-ness was channeled through all of the characters she portrayed.) But whatever else The Brown Bunny is, it’s a painstaking visualization of a bitter sexual fantasy. Hypnotized by the sound of the asphalt softly whirring by under his tires, addled by the memory of a great lost love, and racked with guilt, Bud Clay is on a road trip to rendezvous with ghosts.

Posted by on August 27, 2024 6:00 PMGet The Brown Bunny on Blu-ray from Amazon.com

The Brown Bunny" title="Still from

The Brown Bunny" title="Still from